#

Discovering our Universe

#

Foreword

We shall not cease from exploration.

And the end of all our exploring.

Will be to arrive where we started.

And know the place for the first time

-- T. S. Eliot

The purest goals of science are to understand more about ourselves, about the things around us, about our origins. Achieving this is perhaps not as practical as inventing a machine to do things more efficiently, or as critical as developing a drug to fight a disease. Such goals however are meaningful in shaping the way we think, and help us to find optimal solutions to coexist and connect with the world we live in.

At the end of this lesson, you should be familiar with the terminologies, history and early models of our Universe. You will also begin to understand astronomy as a scientific discipline based on observational evidence. Finally, you will be introduced with the basics of telescopes and use one to look at celestial objects.

Before the lecture, you will self-learn some astronomy through

#

1.1 Pre-Lesson Homework

#

1.1.1 Terminologies

There are many terminologies peculiar to the field of astronomy. It is useful to get yourself familiar with them before going deep into the science. Do an online search to understand the terms below and write a short sentence for each to explain its meaning.

#

1.1.2 Stellarium

Download the programme Stellarium

Launch Stellarium.

Move the mouse to the lower left corner of the screen to reveal the status bar.

Click on the Location Window icon at the top of the status bar on the left to set your location to Singapore (Google to find the Longitude and Latitude of Singapore and ensure that Stellarium is correct).

Below the Location Window icon, click on the Date/Time Window to the set date and time to your current (or preferred) time and date.

In the Sky and viewing option window (or press "F4"), set the light pollution to 7.

Move your screen to a portion of the night sky you like. Finally, go to the Configuration window (or press "F2"), then click on "Save Settings" to keep all these changes.

Click and drag by mouse to tour around the sky. You may also use the arrow keys. Zoom in and out by scrolling on the mouse wheel, or by pressing Ctrl + Up or Down arrows.

#

1.1.3 Telescope

Read the SPS telescope manual (for Nexstar 6SE).

#

1.2 Past models of our Universe

#

1.2.1 Mapping the Stars

Humans have been mapping out the stars for a very long time. Several ancient architecture, artifacts and drawings were designed with reference to the positions of celestial objects. These objects could be made to record and study the seasons (to optimize agriculture activities), for navigation, or even for religious and political purposes. A few examples are listed below.

](<resources/Chapter 1/Nebra.jpg>)

#

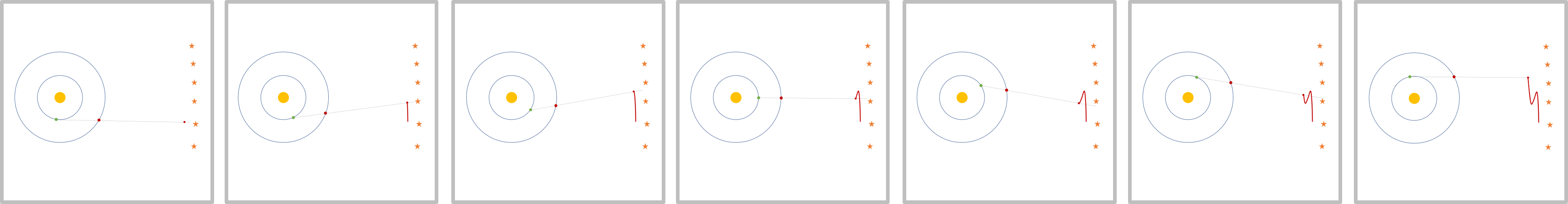

1.2.2 Geocentric, Static Earth and Perfect Circles

Greek philosopher Plato (424--348 BC) and later his student Aristotle (384--322 BC) advocated a model where the Earth is at the center of the Universe, while the Moon, Sun and planets orbit in concentric circles around Earth. Although now we know that this model is wrong, what the ancient Greeks did was still highly commendable. They tried to make sense of the periodic motion of planets and Sun along the ecliptic with a physical model. The act of doing so is aligned with modern scientific thinking and processes.

It should also be noted that not all Greek philosophers believed in the geocentric model. The Pythagorean school of thought believed that the Earth, the planets and the Sun are orbiting around a "central fire". Aristarchus (310-230 BC) proposed the first heliocentric model where the Earth orbits the Sun. These models were generally sidelined in favour for the more influential Aristotlean school of thought.

If Earth is moving,

then one should observe some stellar parallax (shift in position of a nearby star against the background).

However as no stellar parallax had been observed in ancient times, it was logical to conclude that Earth is static.

There were unsurprisingly some elements of mysticism in the early models. It was believed that circles and spheres are geometrically perfect, and thus the motion of heavenly bodies must be in perfect circles.

#

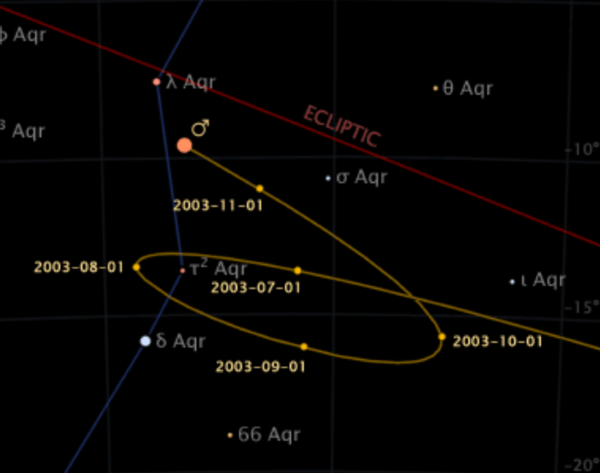

1.2.3 Retrograde Motion of Planets

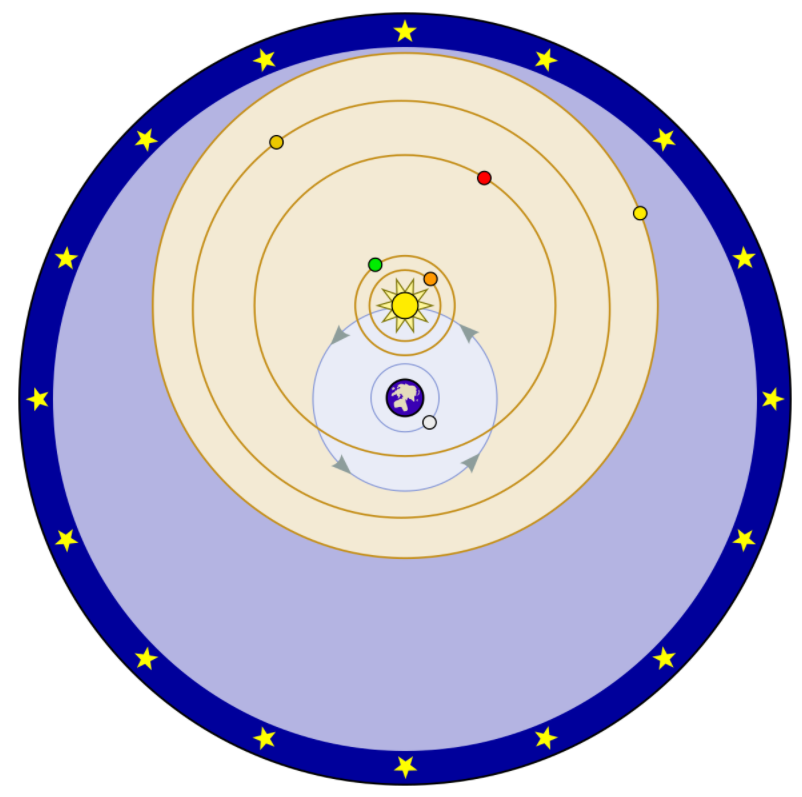

While the geocentric model generally accounts for the observed motions of celestial bodies, it could not explain an anomalous behaviour of planetary movement known as retrograde motion. Planets generally drift from east to west along the ecliptic over the year. But sometimes they appear to move backwards for weeks or months, before continuing back in the usual direction.

#

1.2.4 Ptolemy's Solution: Circles within Circles

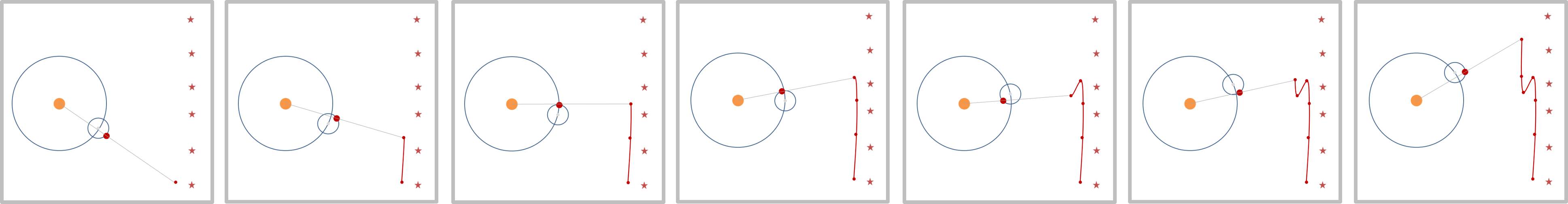

Claudius Ptolemy (AD 100-170), Roman/Greek/Egyptian mathematician and geographer made an ingenious twist to the geocentric model to allow the model to fit observational data better. To the original circular orbit of a planet which he called the deferent, he added a smaller circle called the epicycle. The center of the epicycle is on the (circumference of the) deferent, and the planet is on the (circumference of the) epicycle.

While the epicycle moves clockwise along the deferent, the planet moves clockwise along the epicycle. When the (linear) direction of motion in the epicycle is opposite to that in the deferent, retrograde motion occurs.

This circle within circle model allowed Ptolemy to have another set of independent parameters: radius and period associated with the epicycle. In more modern terms, Ptolemy decomposed a complicated periodic motion (derived from astronomical observations) into two simple circular periodic motion. Does this sound like something you have learned before?

Speaking of sound, to visualise with our ears Ptolemy's trick, run the following in Wolfram|Alpha.

play sin(880 pi t) for 10 splay sin(880 pi t)+0.1{*}sin(440 pi t) for 10 sThe first sound \sin(880\pi t) you hear is analogous to the original geocentric model with 1 circle. The second sound \sin(880\pi t)+0.1\sin(440\pi t) is analogous to Ptolemy's geocentric model with an epicycle. Hear for yourself to note the difference.

#

1.2.5 Heliocentric model

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) published On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres in 1543, where he re-proposed the heliocentric (Sun-centered). Earth was treated as just another planet doing circular orbit around the Sun. He arranged the planets in order of distance from the Sun using the period of orbit he calculated. Earth was the third rock from the Sun, after Mecury and Venus, before Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. He also used geometry and observational data to estimate the relative distance from the Sun for different planets.

The elegance of the heliocentric model comes from its ability to demonstrate retrograde motion of planets in a simple way. Retrograde motion of a planet can be observed around the time when it is at it's closest distance to Earth.

Unfortunately, despite the elegance, Copernicus' model cannot account for the observational data very well when it comes down to numbers. To match the numerical data, he had to add epicycles to the heliocentric orbits! This is one of the main reasons why many were skeptical of Corpernicus' heliocentric model..

#

1.2.6 Tycho Brahe's Observations

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) was the most respected astronomer of his time. He took pride to make systematic and careful astronomical observations. One of his early works was the sighting of a supernova in the constellation of Cassiopeia in 1572. Tycho Brahe used this as evidence to challenge the Aristotelian view that the heavens is unchanging,

He was offered an island by the Danish king, on which he built an observatory and alchemy research centre. There, he constructed several custom built (non-telescope) astronomical instruments capable of measuring positions of celestial objects to 40'' (arcseconds!), which far surpassed his contemporaries. The bulk of his observational data was compiled compiled by Johannes Kepler in the Rudolphine Tables published in 1627, several years after his death.

Brahe knew about Copernicus' heliocentric model and appreciated its elegance but could not accept a moving Earth. He could not measure stellar parallax, even with his accurate instruments. He maintained a static Earth centered model where the Moon and Sun orbit the Earth while the other planets orbit the Sun.

Tycho fell out of favour with the new Danish king and moved to Prague to begin work as Imperial Mathematician.

#

1.2.7 Johannes Kepler and the Laws of Planetary Motion

In 1600, Prague, Brahe employed Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician, to work on mathematical modelling to fit his observational data of planetary motion. One year later, Brahe passed away and Kepler was appointed as Brahe's successor and continued to work on the project. Instead of using Brahe's geo-heliocentric model, Kepler adopted a modified version of Copernicus' heliocentric model. Kepler found that the data will fit very well in a heliocentric model if the planetary orbit follows an elliptical path instead of a circular one.

In 1609, he published two laws of planetary motion and in 1619, he published the third law. The laws are:

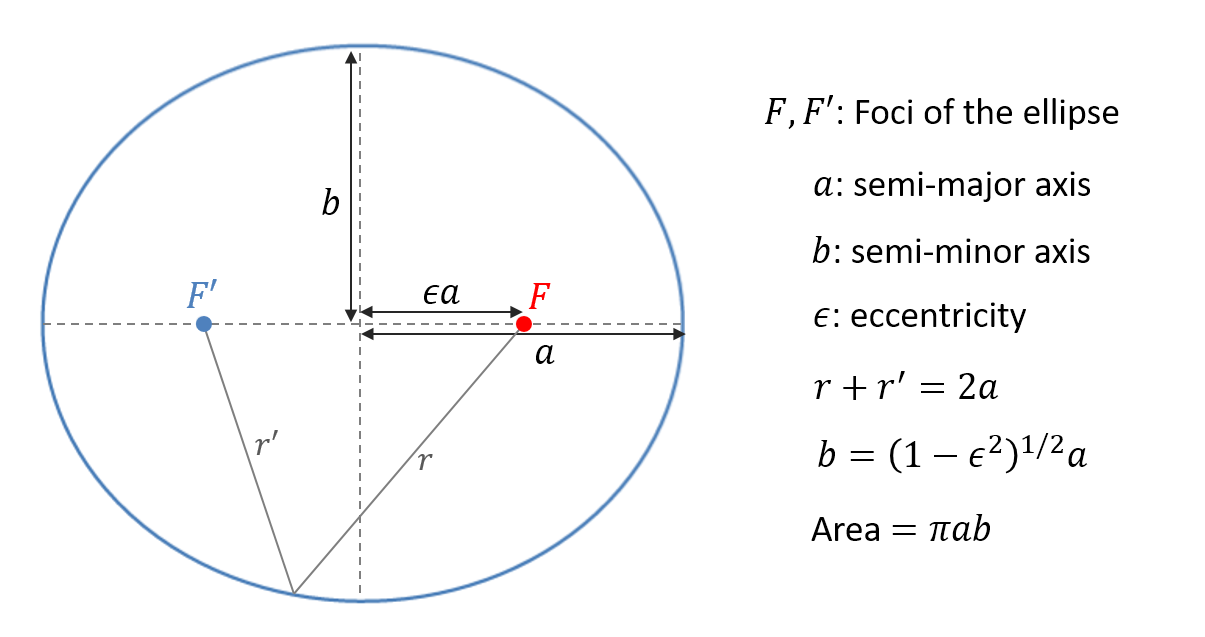

- Law of ellipses: The orbit of each planet is an ellipse, with the Sun located at one of its foci.

- Law of equal areas: A line drawn between the Sun and the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times as the planet orbits the Sun.

- Harmonic Law: The square of the time taken for a planet to complete one revolution about the Sun (relative to the stars) is directly proportional to the cube of the semimajor axis of the planet's orbit.

Mathematically, the equation of an ellipse in polar coordinates (r,\theta) is given by

r=\frac{a(1-\epsilon^{2})}{1+\epsilon\cos\theta}where a is the semi-major axis which is the longest line from the center of the ellipse to its circumference, and \epsilon is the eccentricity, which characterises how elongated the ellipse is.

The second law can be expressed mathematically by

\frac{dA}{dt}=\text{constant}It gives information of how fast the planet is moving at different parts of the orbit.

It was later known that the second law is equivalent to the law of conservation of angular momentum. Interested reader may refer to the appendix for details.

The third law relates the sizes and periods of orbits for different planets.

\left(\frac{T_{1}}{T_{2}}\right)^{2}\propto\left(\frac{a_{1}}{a_{2}}\right)^{3}It is interesting to note that Kepler published the first and second law in 1609 using only data from Mars. The third law was published much later in 1619 after a long attempt to find patterns that could represent ''universal music'' , an old philosophical concept that movements of celestial bodies follow some beautiful proportions, like the proportions that give rise to musical notes.

#

1.3 Introduction to Telescopes

#

1.3.1 Purpose

A telescope is an astronomer's tool to observe faraway objects. It is an optical instrument that utilizes lenses, mirrors or a combination of both. The primary aim of a telescope is to gather more light than the unaided human eye can gather and by concentrating them, allow us to see fainter objects in the distance. For instance, while the four Galilean moons1 of Jupiter cannot be easily seen by the naked eye since they are too faint, most telescopes will enable us to view them. Another important feature of telescopes is their resolving power, which allows telescopes to distinguish clearly between closely spaced objects. This is particularly useful if we want to view individual objects clearly. A case in point will be using telescopes with large resolving powers to resolve galaxies to see that they are made up of millions of stars.

A common misconception is that telescopes are used for magnifying objects. While telescope do magnify an image, this is not the primary reason that they are useful. A small unclear image will only magnify to become a big unclear image. Furthermore, because the amount of light used to create the original image remains the same, as the light spreads over a larger area, resulting in a fainter (magnified) image. In practice, magnification of an image is done by changing the eyepiece of a given telescope.

#

1.3.2 Optical tube designs

Telescopes come in various types in terms its optical tube and mount. Each design comes with its set of advantages and disadvantages. Depending on the nature of observation, one particular type of telescope or mount may be preferred over the others. In general, telescopes can be classified into two types, namely Refractors and Reflectors. There are also two kinds of mounts, namely the Altitude-Azimuth (Alt-Az) and Equatorial mounts.

#

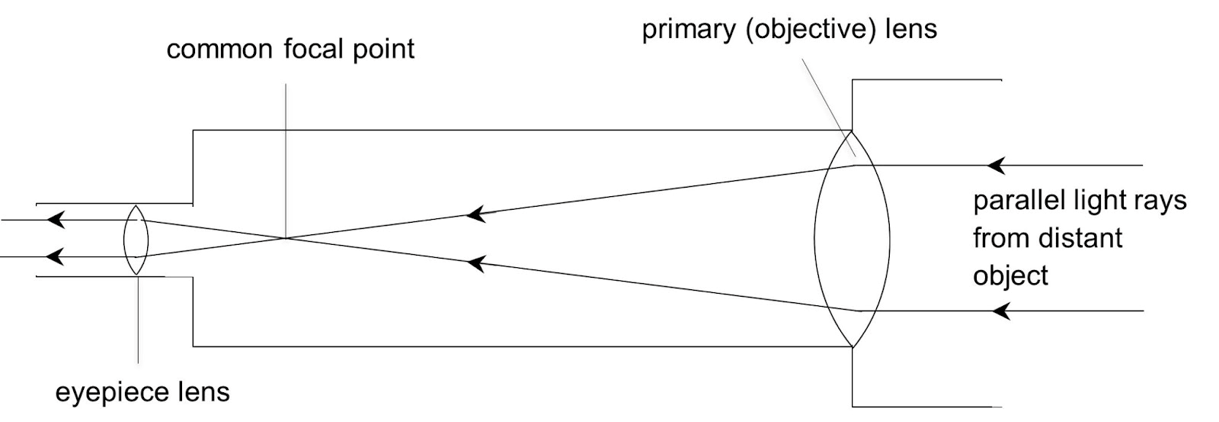

Refractors

A refracting telescope makes use of specially designed lenses to bend light from a distant object to a focus and form an image. The earliest telescopes made in the 1600s were refracting telescopes. The figure above shows how light rays are bent in a Keplerian refracting telescope. In a refractor, parallel light rays from a distant object are first focused with the help of a primary (objective) lens, creating a real inverted image at the common focal point. This image is then magnified with the help of the lens in the eyepiece.

Often, refractors are characterized by their long and slim optical tubes due to the long focal lengths of their primary lenses. A long focal length shortens the view of vision but improves magnification with the eyepiece, making refractors ideal for observing closer and bright objects such as the Moon and planets. Since the optical tube is sealed off from the outside, effects due to external factors such as air currents and changing temperatures that can disturb the image capturing process are eliminated, producing steadier images. This also means that the optical components in a refractor require minimal maintenance and cleaning.

A disadvantage of refractors is that lenses can be heavy and costly. While a larger primary lens allows for larger light-gathering power and resolution power, it will also be more expensive to construct and weigh more. Moreover, a longer optical tube will also be required to bring the light rays into focus. This means that refractors with larger lenses and hence larger aperture sizes or diameters tend to be heavier and quite expensive.

#

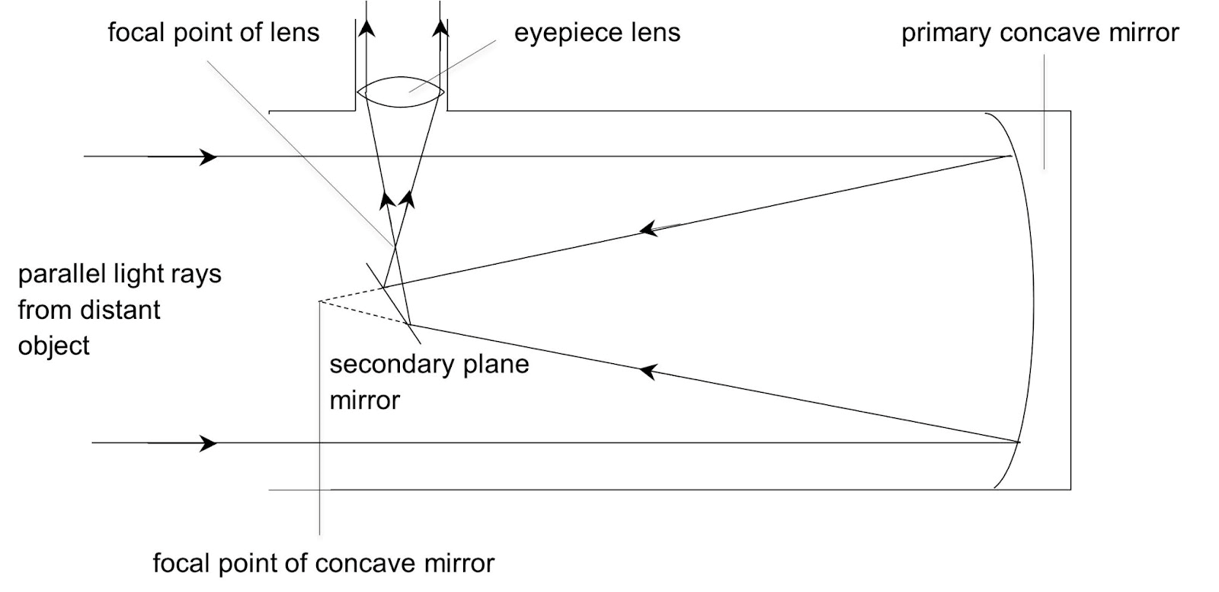

Reflectors

As its name implies, a reflector telescope makes use of curved mirrors that reflect light to a focus. The telescope was first introduced by Isaac Newton in 1668 and thus also called a Newtonian telescope. The figure above shows how light rays are reflected in a Newtonian telescope. Parallel light rays from a distant object are first reflected off a primary concave mirror before reflecting off the secondary plane mirror, producing a real inverted image at the focal point of the eyepiece lens.

Reflectors are commonly preferred over refractors due to several reasons. Mirrors are easier to construct and less expensive than lenses. Mirrors, no matter how large, are also generally thinner and weigh less compared to lenses of the same sizes. While lenses require support only at their edges, mirrors can be supported against a surface at its back. This means that primary mirrors in reflectors can be made extremely large, making them ideal for gathering light and achieving superior resolving power.

Reflectors are not without their disadvantages. Because they use open optical tube assemblies, the mirrors in reflectors must be cleaned periodically and realigned (collimated). An improperly aligned telescope may result in blurry or distorted images. Moreover, the large reflecting surface of the primary mirror may become tarnished when exposed to open air after years of usage.

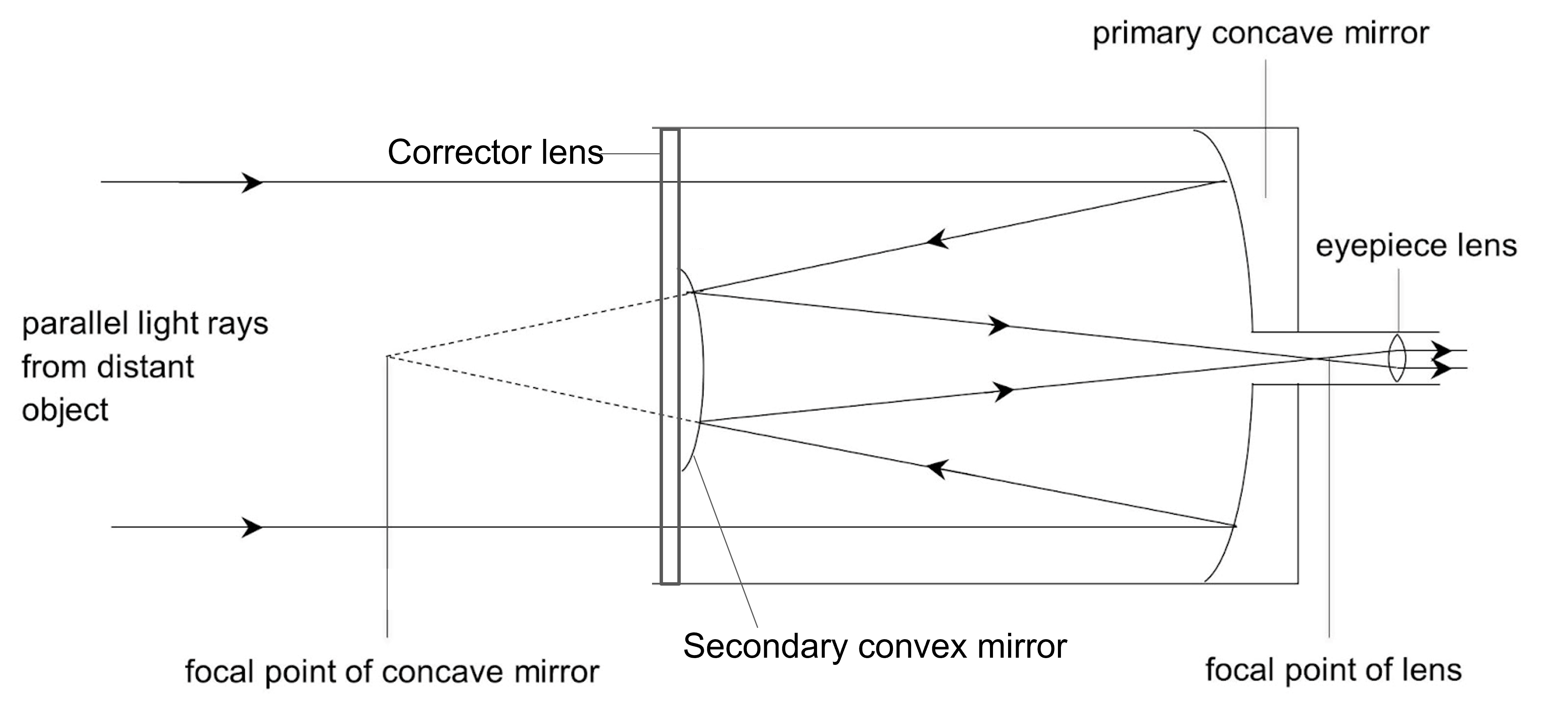

The Schmidt-Cassegrain is an upgraded version of the Cassegrain, a reflecting telescope introduced in 1672 by the French priest Laurent Cassegrain. Similar to the Newtonian reflector, it makes use of a concave primary mirror but uses a convex secondary mirror instead. The secondary mirror reflects the beam back towards the primary mirror, where it passes through a hole bored in the center of the mirror and comes to a focus just below it. This allows the focal point to be much more accessible and enables the scope to be made much more compact to a Newtonian reflector. The Schmidt-Cassegrain differs from the usual Cassegrain by having an additional corrector lens at the front of the telescope. The purpose of this lens will be discussed later.

#

1.3.3 Telescope Mounts

A telescope's optics is only half the story. A telescope mount is just as important as the optics since it must not only hold the scope steadily, but allows it to point anywhere in the sky smoothly and easily. In general, telescope mounts can be classified into Alt-Az and Equatorial mounts.

An Alt-Az mount is the easier one to construct. It allows for movement in two angular directions. At your position on Earth, the mount allows the telescope to move vertically about the altitude axis and horizontally about the azimuth axis. Although easy to set-up, it has the drawback that tracking accurately a distant object such as a star or galaxy requires the telescope to be driven in both axes simultaneously at varying speeds. However, another limitation is that the image will rotate as the telescope tracks, and therefore during photography the detector must also be counter-rotated during any exposure in order to produce an un-trailed image.

If one axis of the mount is made parallel to the Earth's rotation axis (Earth's Polar axis) and the other axis (declination axis) is perpendicular to this, then the mount is known as an Equatorial Mount. The mount allows the telescope to move in the direction of the Celestial North and South poles as well as east-west (Figure 4b). This has the advantage that once the telescope is pointed at a particular star or galaxy, then tracking of the object as the Earth rotates is achieved simply by moving the telescope at a constant speed around the polar axis only. Moreover, the image does not rotate as the telescope tracks. However, the Equatorial mount is more difficult to set up as it requires accurate alignment. In the Northern Hemisphere, this can be done by aligning the scope to the North star Polaris2. If Polaris is not visible because you are on the Equator (e.g. Singapore) or in the Southern Hemisphere, alignment can done on a computerized mount by aligning the scope to a star whose coordinates on the celestial sphere are known.3

The equatorial mount requires stronger motors and sturdier mechanical design since gravity pulls the mount at an angle. As such most large telescopes uses the Alt-Az mount.

Ex. Can you determine which type of scope and mount the SPS telescopes use?

#

1.3.4 Limitations

It is important to be aware that telescopes, like all other instruments, come with their limitations and some of them can differ across designs.

#

Resolving Power

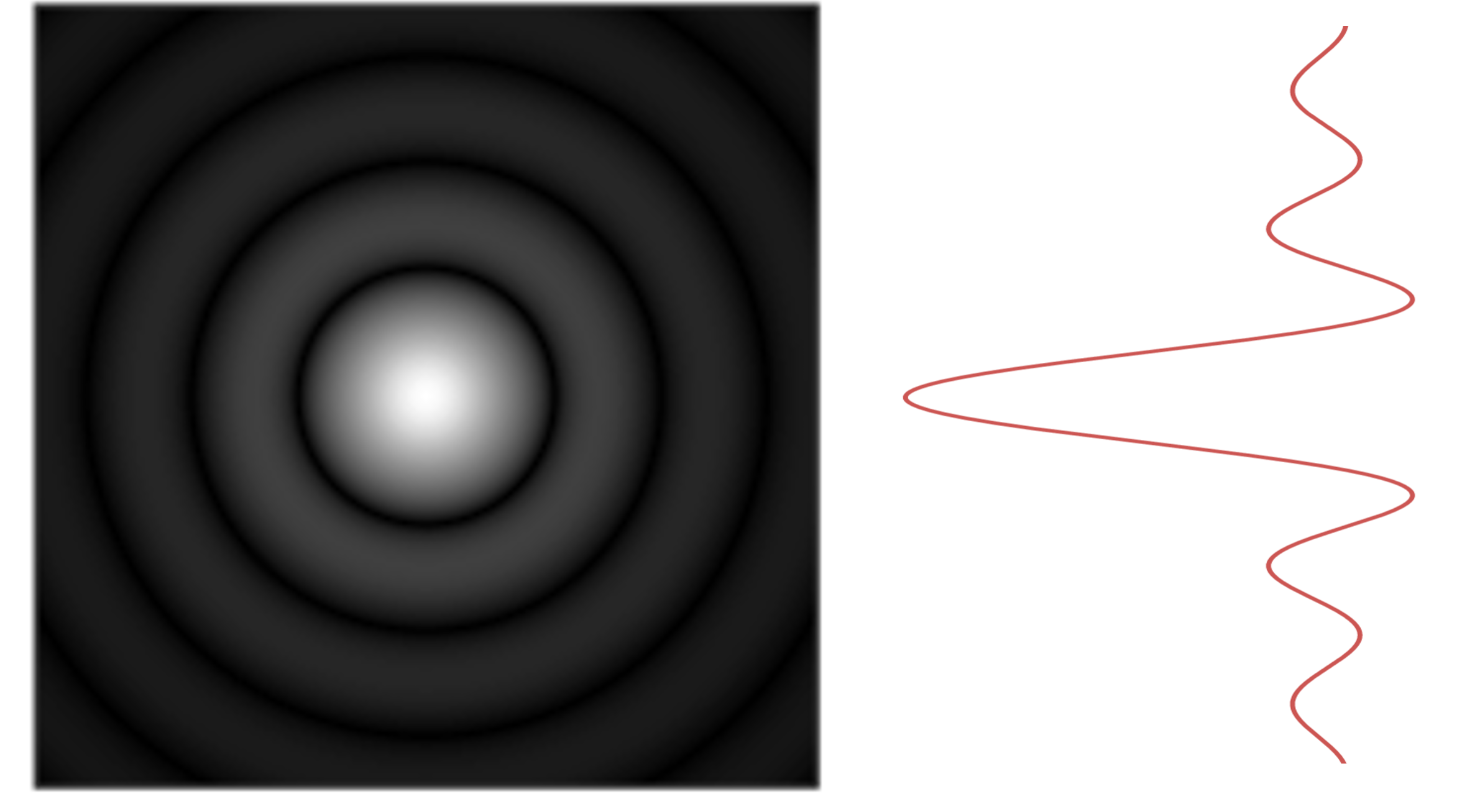

No matter how good the optics of a telescope is, it has a limit to which it can allow us to distinguish closely-spaced objects. In the last chapter, we learn that the wave nature of light causes it to diffract and bend around obstacles. This disruption causes light waves to run into one another, interfering constructively and destructively. Much like how light is diffracted when passing through a single slit and causing the waves to form interference fringes, the circular opening of a telescope creates a circular interference pattern.

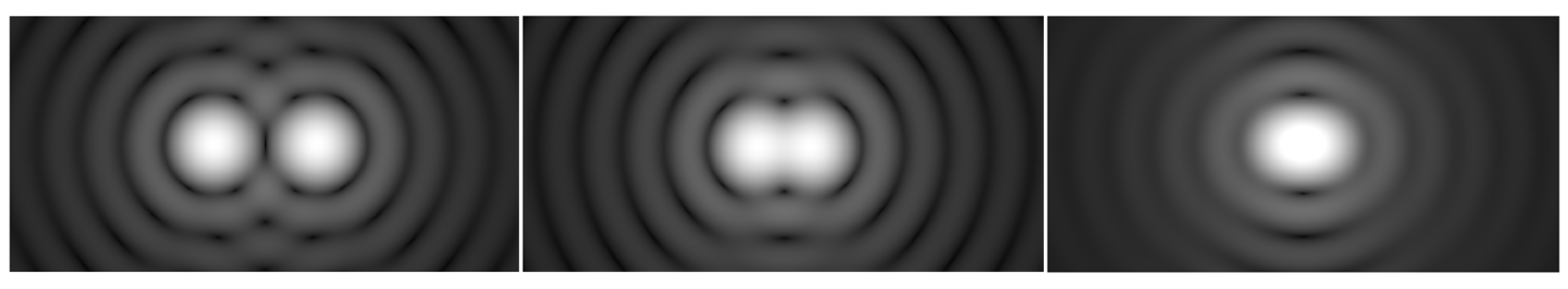

A circular aperture is much like a single slit but exists in two dimensions instead of one. Because of this, when you make an image of a distant star, light from the star does not focus into a single point. Instead, if you use an eyepiece with high magnification, you will see a disk with faint rings around it (see figure above). The bending of light caused by the circular aperture of your telescope results in light waves interfering to form such an interference pattern, popularly known as the Airy Disk. The angular radius \theta of the Airy disk is given by

\sin\theta=1.22\frac{\lambda}{D}where \lambda is the wavelength of the light and D is the diameter of the telescope aperture (size of the objective lens/mirror).

If two celestial objects have an angular separation of more than \sin^{-1}\left(\dfrac{1.22\lambda}{D}\right), the two objects can be clearly seen. We say that the image of the objects are resolved. Conversely if the angular separation is less than \sin^{-1}\left(\dfrac{1.22\lambda}{D}\right), the objects will be seen as a single fuzz.

We see that, for a fixed primary lens or mirror the telescope uses, the size of the Airy Disk depends solely on the diameter of the circular aperture, or equivalently the diameter (D) of the primary lens or mirror in your telescope. This means that as the diameter of your scope increases, the resolving power of your scope increases and you are able to distinguish between stars that are closer together.

Also note that if the telescope is designed to see in higher wavelengths (\lambda), the Airy disk will be larger as well. This is the reason why radio telescopes need to be much larger than optical telescopes.

The angular size of the Airy disk for a telescope is commonly called the diffraction limit of the telescope.

#

Aberrations

Aberrations refer to defects in images that may occur as a result of the limitations in the design and manufacture of a telescope's optics. They may also occur in accessories such as eyepieces. Common examples of aberrations include chromatic aberration, spherical aberration (i.e. coma and astigmatism), field curvature and distortion.

Chromatic aberration is the failure of a lens to bring all wavelengths of visible light into a common focus. It is usually seen as a violet halo around bright stars or fringes around bright objects such as the Moon. Since different wavelengths of visible light are refracted to different degrees (i.e. blue light refracts more than red light) by a single type of glass, light coming through a lens can be focused at different locations depending on their wavelengths; one wavelength may be focused while the other wavelengths will be out of focus. This is commonly experienced in refractors since they use lenses as their primary objectives. To reduce chromatic aberrations, extra-low dispersion glasses such as fluorite is commonly used in lens making and specially designed lenses known as achromats are usually used alongside the primary objective lens for correction.

Spherical aberration refers to the failure of light rays passing at different distances from the center of a lens or mirror to come to a focus. Often, light rays through the edges of a lens or mirror focus closer compared to rays near the principle axis. This occurs more for optical systems with low f-number and results in distant objects such as stars looking like blurred discs. To fix this type of aberration, mirrors in Newtonians are often designed precisely with parabolic curves. Primary lenses in refractors must be of the right shape to minimize this error, usually with a more highly curved front surface facing the sky.

Coma and astigmatism are two special kinds of spherical aberrations. Coma refers to light rays from a lens or mirror focusing off-axis. The image shows up as little off-axis comet-shaped blobs that point inwards towards the center of the field and get bigger as you look towards the edge of the field of view. Astigmatism is another off-axis effect caused when light rays are focused to different focus points in the vertical and horizontal plane. It elongates images horizontally and/or vertically, making them look cross-like. Coma is usually corrected the same way spherical aberrations are reduced in the design of the main scope while astigmatism is corrected with additional lenses or lens elements to increase f-number.

Field curvature occurs when an extended object or stars in the field of view of a telescope do not focus on a flat surface. An object in the center may be focused while others farther out are not. Similar to astigmatism, it is usually corrected with additional lenses or lens elements to increase the f-number.

#

Atmosphere

The atmosphere is one of the major limitations when it comes to using telescopes on Earth. No matter how well a telescope is perfectly designed, the atmosphere diminishes and scatters light such that the faintest and finest details are always just beyond our reach. Dust and water can reduce the amount of light transmitting through our atmosphere. Moreover, the effects of turbulence greatly affect the object being observed through a telescope. Air turbulence refers to pockets or layers of air of different temperatures and hence, densities, between the telescope and the distant object. This results in changes of the refractive index of air at these air pockets and layers, causing light to undergo refraction repeatedly. As a result, stars and distant objects may appear to "jitter" or jump around when viewed through a telescope. Our eyes often perceive this as 'twinkling' and images captured may appear smeared. While some telescopes have been designed to counteract the effects of this 'twinkle', the images captured, although improved drastically, will never match those captured by a telescope in space, where the effects of the atmosphere are totally eliminated.

#

Size and weight

Because of their mounts, telescopes are also limited in their sizes and weight. The payload limit of the mount refers to the maximum weight which the mount can safely carry. If the entire weight placed on the mount is too heavy, the mount may fail to track and tip over. The size limit of the mount refers to the largest telescope the mount can carry. If the telescope is too large or too long, it may hit something or the mount may not balance properly during tracking. Storage may also become a problem if the telescope is too large. In general, Alt-Az mounts offer a larger payload and size limit. These mounts are usually lightweight and compact since they can be built smaller, making them easier to carry and store. On the other hand, equatorial mounts have lower payloads and size limits since they come with extended counterweights, which are as heavy as telescopes. They therefore require more space for their counterweights to swing and are more difficult to carry and store. While a telescope with a larger aperture offers more light gathering power and a higher resolution power, it comes at the expense of being much bigger in size and heavier which are limited by the payload and size limit of the mount it uses.

#

1.3.5 Reading a telescope specifications

Aperture - The aperture refers to the diameter of the primary (objective) lens or mirror of the telescope. It is usually stated in millimeters (mm) or inches ('').

Focal Length - The focal length refers to the length over which light rays passing through the primary (objective) lens or mirror come to a focus on a (focal) plane. It is also stated in millimeters or inches. An image of a distant object will be visible on a screen placed on the focal plane.

Magnification - This is a measure of how much an image is magnified to our eyes and is controlled by the eyepiece we use. The eyepiece also has a lens and its focal length. Magnification of a telescope is calculated by taking the ratio of the focal length of the objective lens or mirror to the focal length of the eyepiece.

F-number (focal ratio) - This refers to the ratio of the focal length of the objective lens or mirror to the diameter of the aperture. A large focal ratio implies smaller aperture, lower light gathering power as well as a narrower field of view (vice versa). For example, a telescope whose primary (objective) focal length is 5 times that of its aperture diameter has a f-number (focal ratio) of f/5.

Resolving Power - This is the measure of the ability to distinguish clearly small details of an object or two closely spaced from each other. The larger a telescope's aperture, the smaller the minimum resolvable angle between two distant objects and the larger its resolving power. Resolving power can be calculated from Equation and is usually expressed in arcseconds.

#

1.3.6 Other wavelengths

Telescopes are not limited to the visible light of the electromagnetic spectrum. In fact, astronomers use a number of telescopes sensitive to different portions of the spectrum to study objects in space. The following lists examples and some of their main uses.

Radio telescopes - Since radio waves are transparent to Earth's atmosphere, they are used for interferometry where a satellite and a ground-based telescope correlate their signals to simulate a radio telescope the size of the separation between the two telescopes. Mainly used to study star birth during the early universe. Examples: Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) that is ground-based and Spectr-R that is space-based.

Microwave telescopes - Primarily used to study the Cosmic Microwave Background. Examples include Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) and Planck.

Infrared telescopes - Infrared radiation is limited by Earth's atmosphere and such telescopes are best sent to space or used on mountaintops where the atmosphere is thin. Used to study stellar nurseries, nebulae and red-shifted galaxies. Examples include the James Webb Space Telescope, Herschel and Spitzer Space Telescope.

Optical and ultraviolet telescopes - These wavelengths are also limited by Earth's atmosphere and the best images are only captured in space. Used to study a wide variety of objects including planets, stars, galaxies, galaxy structures, planetary nebulae and protoplanetary disks. Domestic telescopes are optical telescopes. A famous telescope that uses optical and ultraviolet wavelengths is the Hubble Space Telescope.

X-ray telescopes - Since X-rays are blocked by Earth's atmosphere, telescopes are mainly space-based. Primarily used for detection of black holes, supernovae remnants, galaxy clusters, some binary stars and neutron stars. Examples include X-ray Multi Mirror Mission (XMM) and Chandra.

Gamma ray telescopes - Since Gamma rays are blocked by Earth's atmosphere, telescopes are mainly space-based. Used to detect and study high energy gamma ray astrophysical sources such as gamma ray bursts, supernovae, neutron stars, pulsars and black holes. Examples include Fermi Space Telescope and the Swift Explorer.

#

1.4 In-class activities

#

1.4.1 Activity 1: Crux

Launch Stellarium

Set the time and date to 11 Jan 2022, 1:30 am.

Search for Crux.

Increase the time by the hour until 6:30 am.

What do you observe?

#

1.4.2 Activity 2: Hands-on with Telescope

Refer to Page 1--10 of the Celestron 6SE telescope manual. Set up the telescope and perform a finderscope alignment.

#

1.4.3 Activity 3: Observing the Airy disc

Let's try this the demonstration as described in this paper

#

1.5 Discussion questions

- Why do ancient stargazers call planets "wandering stars"?

- Does the Sun rise in the East? Same position in the East everyday? Use Stellarium to find out! On Stellarium, look to the East. Set the time to around 6:30---7:00 am to see the sunrise. Increase the date by a month repeatedly. Does the position of sunrise change over the year? Describe your observations

- It takes 365 days for Earth to complete 1 revolution (2 \pi radians) around the Sun. What is the angular speed (rad/s) and speed (m/s) of Earth in the rest frame of the Sun?

- Suppose you want to reach Alpha Centauri (nearest star to us) in 100 years. How fast do we need to move? How about reaching Andromeda Galaxy (nearest galaxy to us) in 100 years?

- The Moon's equatorial diameter is 3.476 km and its orbital distance from Earth varies between 356 400 km and 406 700 km. The Sun's diameter is 1390 000 km and distance from Earth ranges between 147.5 and 152.6 million km. Find the Moon's and Sun' angular size at their respective minimum and maximum distance from Earth. Discuss the implications on solar eclipses.

- Suppose that the typical size of a galaxy is 100 000 light years, and typical separation between galaxies is 1 million light years. Also suppose that the typical size of a star is 1 million km, and typical separation between stars is 5 light years. Discuss the implications on stellar and galactic collisions.

- Write a short summary of the evolution of ideas of our Universe from the ancient Greeks to the modern view.

#

1.-1 Appendix

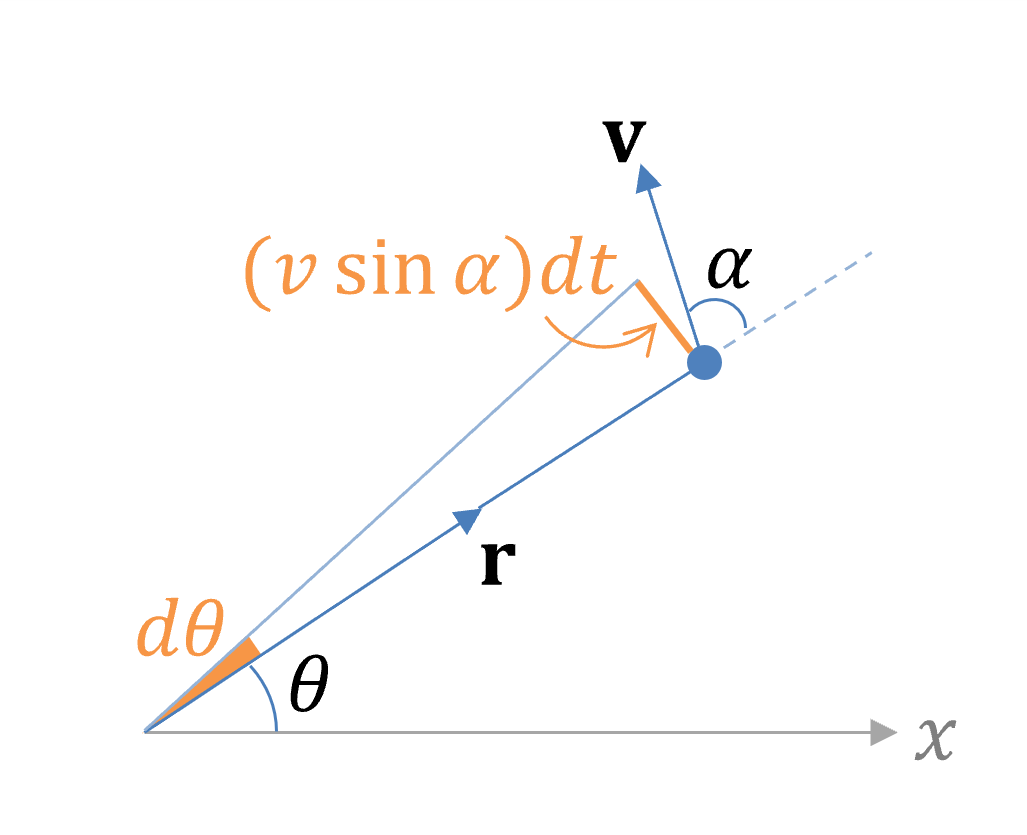

Kepler's second law is in fact conservation of angular momentum L.

Kepler's second law gives

\frac{dA}{dt}=\frac{1}{2}r^{2}\frac{d\theta}{dt}=\text{constant}Angular momentum L is defined by

\mathbf{L}=\mathbf{r}\times\mathbf{p}=m\mathbf{r}\times\mathbf{v}The magnitude of angular momentum is

|\mathbf{L}|=L=mrv\sin\alphawhere \alpha is the angle between \mathbf{r} and \mathbf{v}.

From the diagram above, we see that

v\sin\alpha dt =rd\theta

v\sin\alpha =r\frac{d\theta}{dt}Putting this into the expression for the magnitude of angular momentum, we have

L=mr^{2}\frac{d\theta}{dt}Since Kepler's second law says that

\frac{dA}{dt}=\frac{1}{2}r^{2}\frac{d\theta}{dt}=\text{constant},this implies that

L=2m\frac{dA}{dt}=\text{constant}.-

Polaris (North star) is a star that appears almost directly above the Earth's rotational axis in the Northern Hemisphere (almost near the North Celestial Pole). As Earth rotates, every other star seems to spin around the axis, tracing out a circle in the sky but Polaris appears to stand still.↩

-

In astrophotography where long exposures are needed to image an object, a more precise but tedious manual alignment process known as the Drift Alignment is usually performed. The details of this will not be covered in these notes.↩